Reinvention: A New South End Story

Written by Cyrus Dahmubed | Illustrated by David Tabenken

Hacin engages with bringing history back to life through the construction of new architecture. Over the last 25 years, Boston’s South End has served as a testing ground for this architectural and urban agenda. In particular, three neighboring projects serve as examples of different approaches we’ve taken to achieving this prerogative: A seminal project, Laconia Lofts [completed in 2000], advanced an urban agenda by carefully responding to the city’s historic development; our new home at 500 Harrison Avenue was reinvented as a space for a new generation of workers and designers, just as the building’s original construction was for the company that first built it; and, just across the way at Jordan Lofts, we have transformed the former horse stables of a hallmark Boston department store into a new commercial and residential building that incorporates clever hints of its equine history while also repairing an urban blemish and continuing the neighborhood’s revitalization.

T.S. Eliot and the Spirit of Change

“In my beginning is my end. In succession houses rise and fall, crumble, are extended, are removed, destroyed, restored, or in their place is an open field, or a factory, or a by-pass.” – T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

These words from T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets might easily have been inspired by Boston’s South End, where Eliot was known to pass his time at The Grand Opera House on Washington Street, watching vaudevillian performances and taking in the grit of a rapidly changing industrial neighborhood. That rapid change is easily recognizable in the South End of today, exemplified by the presence of one of Hacin’s most significant projects, Laconia Lofts, which now sits on the site of The Grand Opera. Particularly noticeable in the scale of new construction in the neighborhood’s SoWa district, even the stoic townhouse-lined streets of the old South End have long been characterized by the soft yet unrelenting beat of transformation. This transformation has frequently been at its most impactful when, following the lesson of its context, changes have breathed new life into familiar but forgotten fixtures of the neighborhood’s landscape.

Though the South End has a long history of reinventing itself, its transformation in the last thirty years from a dangerous neighborhood trapped in a frustrating cycle of neglect and disinvestment to one of the most vibrant and beloved parts of Boston has brought with it a resonant architectural character and an effective process of incremental urbanism. Hacin’s work in the South End has long sought to serve as a catalyst for positive change by taking inspiration from the neighborhood’s history, while also embracing that history’s defining traits of rebirth and transformation— just as Eliot may have witnessed them during his time in Boston. Until very recently, this work was done from Hacin’s offices at 112 Shawmut Avenue, with broad views overlooking the Massachusetts Turnpike and many of the city’s core neighborhoods. 112 Shawmut is, itself, a microcosm of the South End’s evolution; built first to serve as a warehouse and factory for a men’s suit company that supplied clothing to the department stores of Downtown Crossing, 112 Shawmut eventually found new life as an office building whose wide open floor plates and abundant natural light were perfectly suited to design studios like Hacin. This particular sequence of transformation is one that has become emblematic of the South End. Buildings built in the late 19th and early 20th century for industrial uses during the neighborhood’s adolescence were vacated as industry left the South End [and Boston more broadly later on], only to find new lives as homes and workspaces for artists, craftspeople, and an increasingly tech-savvy creative population.

David Hacin describes the firm’s move to 500 Harrison Ave as a “return to the heart of the South End”. Like Washington Street, Harrison Avenue, has its own storied history that chronicles the neighborhood’s long transformation from a bay of Boston Harbor to the thriving community of today. These streets are in a unique dialogue with Boston’s pre-Colonial coastline, now buried out of sight beneath the neighborhood, but still present in the form of buildings along Harrison Avenue and Washington St. Hacin’s project, Laconia Lofts, straddles both of these streets and was as transformative to the neighborhood as it was to the office itself [then, housed in its infancy at 46 Waltham Street— another transformed South End industrial building].

“The Heart of the South End”

Since its construction, Laconia Lofts has also served as David’s home and a geographic center of gravity for much of the office’s work in the neighborhood. Despite significant differences – Laconia Lofts was built as a residential building for artists, while 500 Harrison was originally built as the central factory for the Reece Buttonholing and Machining Company – both buildings take their shape from streets that were designed to fit along the old coastline and port.

Through much of the 18th and 19th centuries, the land now known as the South End was an active port called the South Bay. Remnants of the port, which were evident even through the Big Dig, can still be identified today by urban explorers navigating the tail end of Fort Point Channel. The city’s only land connection was the Boston Neck, a narrow isthmus that separated the South Bay from the Back Bay. Running atop this strip was Washington Street, which would grow in prominence and whose crossing with Winter Street would eventually become the city’s downtown.

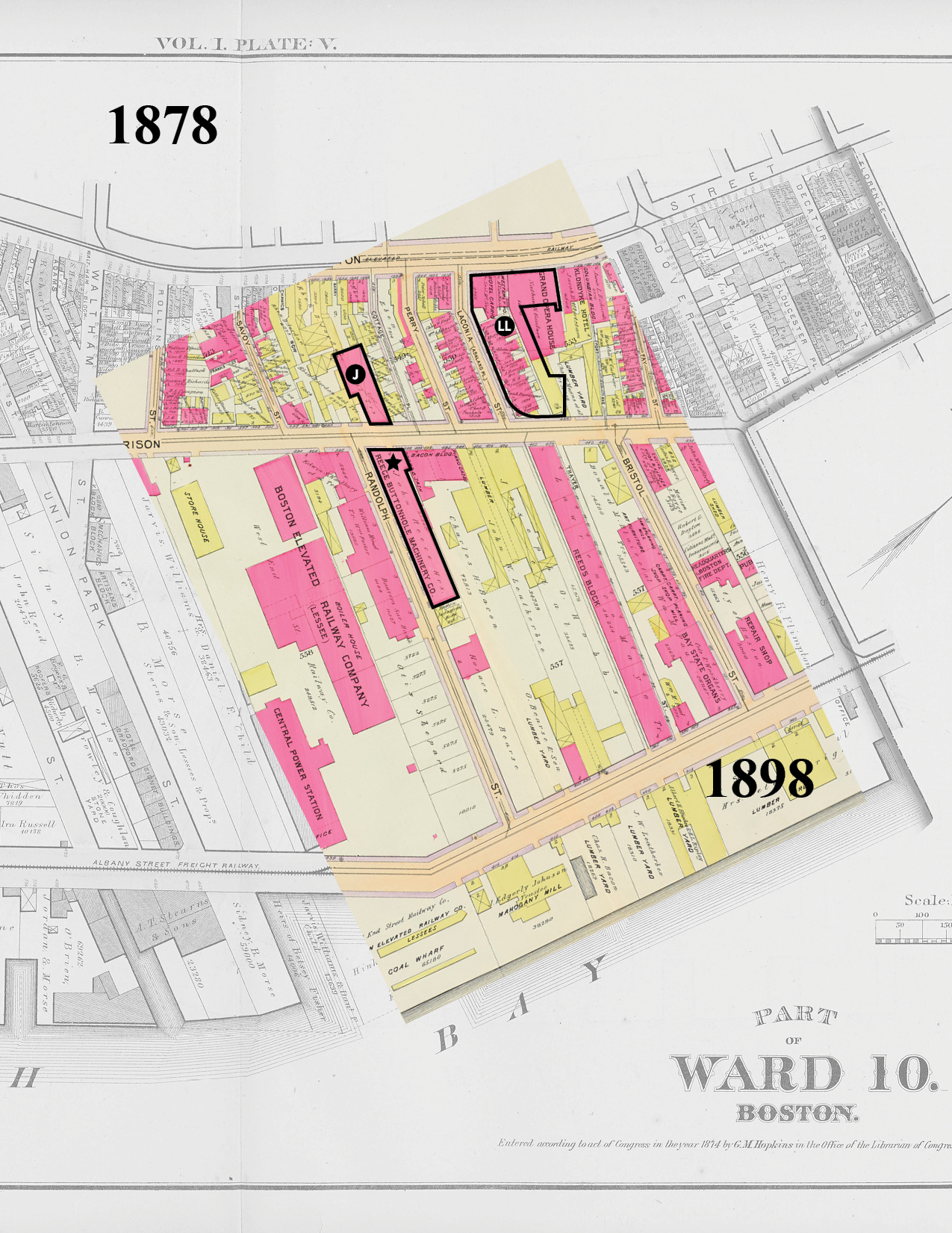

In 1852, Boston’s first City Engineer, Ellis Sylvester Chesbrough —coincidentally my great, great, great, grandfather—was tasked with determining, surveying, and mapping Boston’s original coastline so that the hydrodynamics of the Harbor could be better understood for shipping purposes. A closer look at Boston Neck on the map he produced shows that as the city expanded and the Neck was widened; a line was drawn across the water of South Bay to identify the extent of piers and wharves permissible in order to preserve navigability. The piers in the part of South Bay that would become SoWa were designed to be perpendicular to this imaginary boundary —rather than to existing streets—in order to maximize the water’s usefulness. On land, these piers terminated, obliquely, into Harrison Avenue, forever determining the layout of the 19th- and 20th-century streets that would be built on and around them. These wharves are the ones that still lay beneath three buildings in the heart of Hacin’s South End: Laconia Lofts, 500 Harrison, and the recently completed Jordan Lofts.

Remembering a Boston Icon

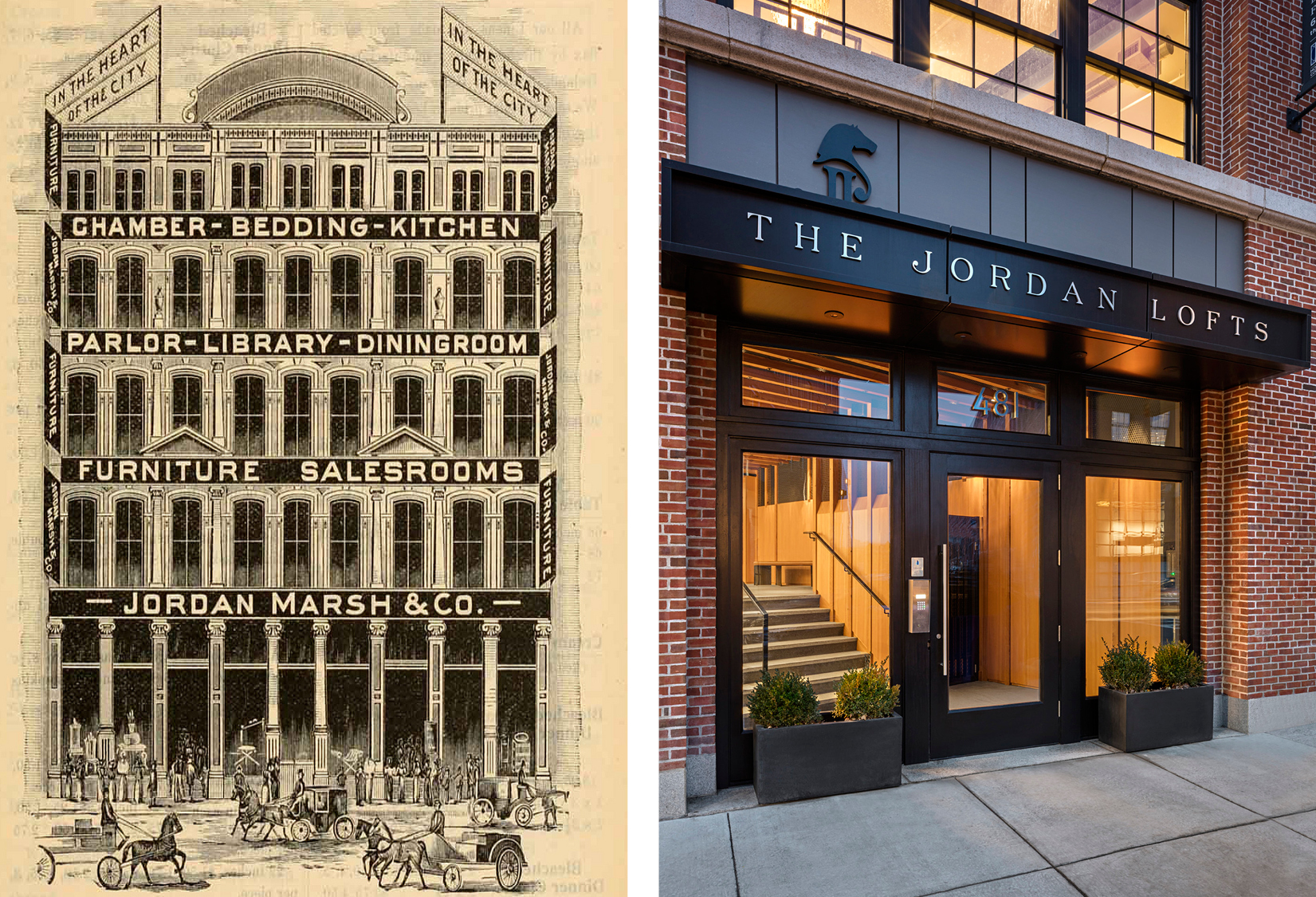

Immediately across from 500 Harrison is Jordan Lofts. Completed in 2016 by Hacin, partnering with developer, builder, and executive architect, The Holland Companies, Jordan Lofts reinvented a building that had originally functioned as stables for the grand dame of Boston department stores, Jordan Marsh. With the layout of the streets around it determined by the same wharves and coastline that informed 500 Harrison’s shape, Jordan Lofts tells the thread of a story within the greater narrative of the South End’s historical tapestry. The Jordan Marsh Company defined Boston’s, and eventually New England’s, shopping scene and its flagship department store in Downtown Crossing was the first of its kind in the country. Like many companies at the time, it maintained a variety of service buildings in the industrial South End to help support the fashionable functions of the store in Downtown Crossing, a link which further bolstered the importance of Washington Street as the city’s major artery. The building that has recently been transformed into Jordan Lofts started its life as a stable for the horses used by Jordan Marsh to deliver goods and transport items between stores.

But this stable was not surrounded by bucolic pasture land; rather the site was hemmed in by everything from manufacturing facilities and lumber storage, to carriage garages and the nearby Grand Opera. As Jordan Marsh transitioned from using horse and buggy to horseless carriage the building ceased to be a stable and was incorporated into a new auto maintenance facility built around its base. Eventually, this function would also give way to a textile warehouse—and later, abandonment—as industry departed the South End and Jordan Marsh partnered with other department stores to create a national conglomerate, the only remnant of which is now Macy’s.

Whereas most of these transitions were largely hidden from the public eye, we sought to make the transformation of Jordan Lofts from an abandoned building into a vibrant residential building apparent to the entire neighborhood. To achieve this, Hacin visibly “spliced” a new volume into the center of the building and expressed it with materials that are set back and differ from the brick of two of the building’s preserved facades. This intervention also helped to transform what had formerly been a “dead” party wall [without allowable windows] into a lively and engaging new façade for the building. Ultimately, this helped to further Hacin’s agenda of incremental urban revitalization predicated on the notion that successful urban revitalization should engage in an open dialogue with its context and history.

Part of this dialogue meant referencing what is perhaps the most unique moment in the building’s history: its period as a stable. To bring this equine history into the 21st-century, Hacin wrapped the building’s lobby in warm, streamlined timber studded with dark wrought iron reminiscent of barns and stables and then introduced art and design details throughout that pay homage to the building’s history with the Jordan Marsh Company. Though wood was introduced into the lobby, modernizing the building for residential usage required the meticulous and laborious removal of the original wood frame structure, and its replacement with a steel skeleton. To execute this Hacin partnered with Longleaf Lumber for the removal, restoration, and reuse of the building’s original heavy timber.

A New Life

Beyond simply bringing Jordan Lofts back to life architecturally, this project also reinforced Hacin and Holland Development’s dedication to the preservation of historic buildings and the building of a new community through residential reprogramming. By transforming these industrial buildings into homes a new, very personal and communal connection is created that repositions their significance to their neighborhood and surroundings—just as their initial use and construction would have done many years earlier. A Jordan Lofts resident and Hacin client, shared appreciation for the historic architecture, saying, “We love the fact that it is a small ’boutique’ building, with only 12 residential units, and respectful of its historic origins…It’s great to be in such a thriving, artistic part of the city.” As buildings transform and their uses change, becoming a place where people live seems to ensure a more certain type of future. Jordan Lofts has had many lives, but now it’s forever tied to the lives of those that reside within it. For me, this brings a special weight and sentimentality to residential architecture and supports the idea that good design can make this relationship to history and place as much part of a home as it is part of the neighborhood.

T.S. Eliot may not recognize the South End of his youth, but there is no doubt that he would recognize its defining characteristic; an ever-present rhythm of rebirth as consistent as the tides that created it.

This is an excerpt from H+ Magazine | No. 5. Featured Image: ©Gustav Hoiland/Flagship photo.